13.2.1. Prey manipulation by predators

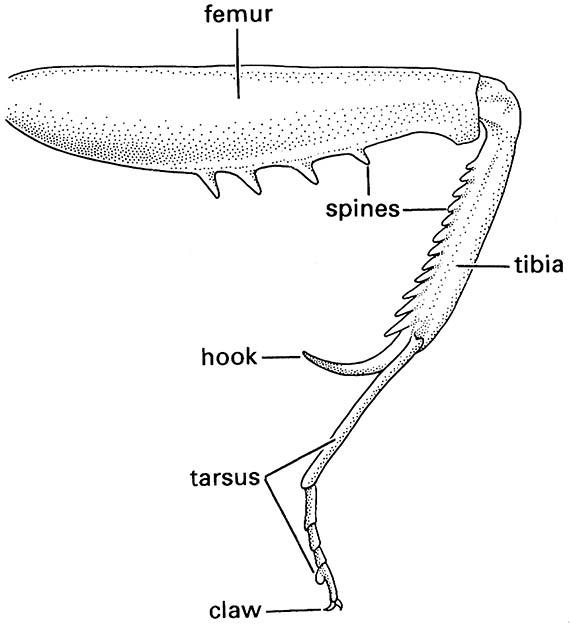

When a predator detects and locates suitable prey, it must capture and restrain it before feeding. As predation has arisen many times, and in nearly every order, the morphological modifications associated with this lifestyle are highly convergent. Nevertheless, in most predatory insects the principal organs used in capture and manipulation of prey are the legs and mouthparts. Typically, raptorial legs of adult insects are elongate and bear spines on the inner surface of at least one of the segments (Fig. 13.3). Prey is captured by closing the spinose segment against another segment, which may itself be spinose, i.e. the femur against the tibia, or the tibia against the tarsus. As well as spines, there may be elongate spurs on the apex of the tibia, and the apical claws may be strongly developed on the raptorial legs. In predators with leg modifications, usually it is the anterior legs that are raptorial, but some hemipterans also employ the mid legs, and scorpionflies (Box 5.1) grasp prey with their hind legs.

Mouthpart modifications associated with predation are of two principal kinds: (i) incorporation of a variable number of elements into a tubular rostrum to allow piercing and sucking of fluids; or (ii) development of strengthened and elongate mandibles. Mouthparts modified as a rostrum (Box 11.8) are seen in bugs (Hemiptera) and function in sucking fluids from plants or from dead arthropods (as in many gerrid bugs) or in predation on living prey, as in many other aquatic insects, including species of Nepidae, Belostomatidae, and Notonectidae. Amongst the terrestrial bugs, assassin bugs (Reduviidae), which use raptorial fore legs to capture other terrestrial arthropods, are major predators. They inject toxins and proteolytic saliva into captured prey, and suck the body fluids through the rostrum. Similar hemipteran mouthparts are used in blood sucking, as demonstrated by Rhodnius, a reduviid that has attained fame for its role in experimental insect physiology, and the family Cimicidae, including the bed bug, Cimex lectularius.

In the Diptera, mandibles are vital for wound production by the blood-sucking Nematocera (mosquitoes, midges, and black flies) but have been lost in the higher flies, some of which have regained the blood-sucking habit. Thus, in the stable flies (Stomoxys) and tsetse flies (Glossina), for example, alternative mouthpart structures have evolved; some specialized mouthparts of blood-sucking Diptera are described and illustrated in Box 15.5.

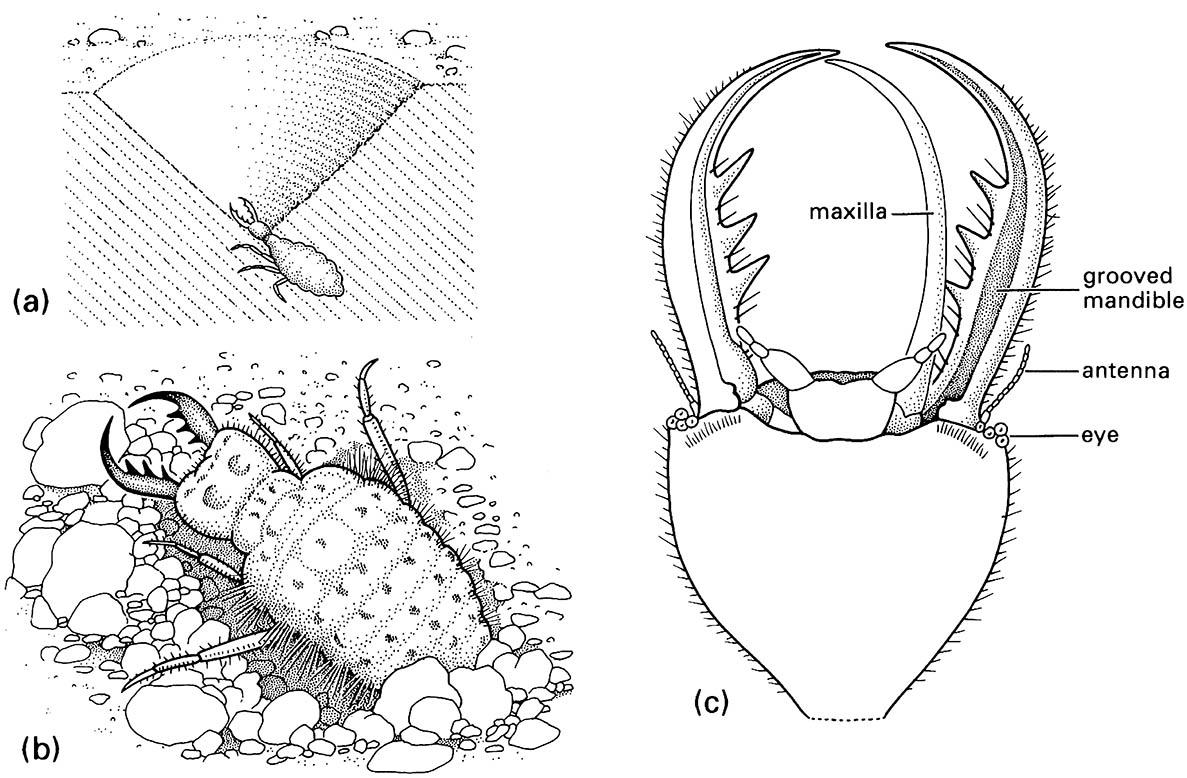

Many predatory larvae and some adults have hardened, elongate, and apically pointed mandibles capable of piercing durable cuticle. Larval neuropterans (lacewings and antlions) have the slender maxilla and sharply pointed and grooved mandible, which are pressed together to form a composite sucking tube (Fig. 13.2c). The composite structure may be straight, as in active pursuers of prey, or curved, as in the sit-and-wait ambushers such as antlions. Liquid may be sucked (or pumped) from the prey, using a range of mandibular modifications after enzymatic predigestion has liquefied the contents (extra-oral digestion).

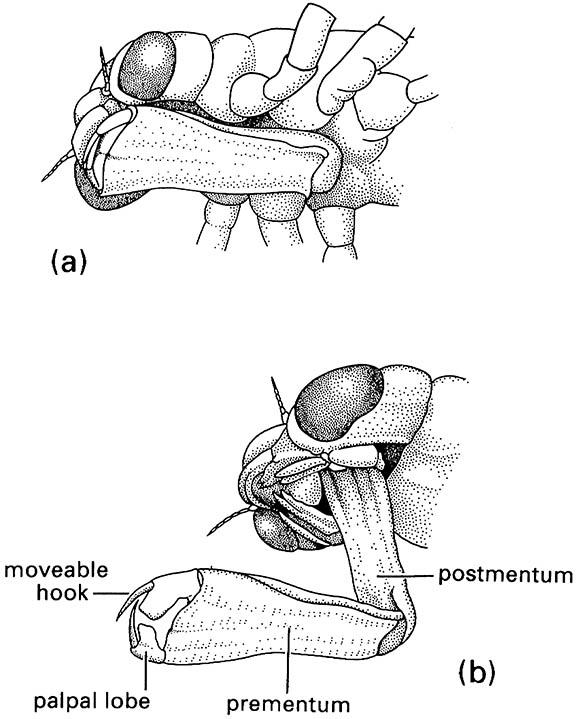

An unusual morphological modification for predation is seen in the larvae of Chaoboridae (Diptera) that use modified antennae to grasp their planktonic cladoceran prey. Odonate nymphs capture passing prey by striking with a highly modified labium (Fig. 13.4), which is projected rapidly outwards by release of hydrostatic pressure, rather than by muscular means.

(After Preston-Mafham 1990)

(a) larva in its pit in sand; (b) detail of dorsum of larva; (c) detail of ventral view of larval head showing how the maxilla fits against the grooved mandible to form a sucking tube. (After Wigglesworth 1964)

(a) in folded position, and (b) extended during prey capture with opposing hooks of the palpal lobes forming claw-like pincers. (After Wigglesworth 1964)